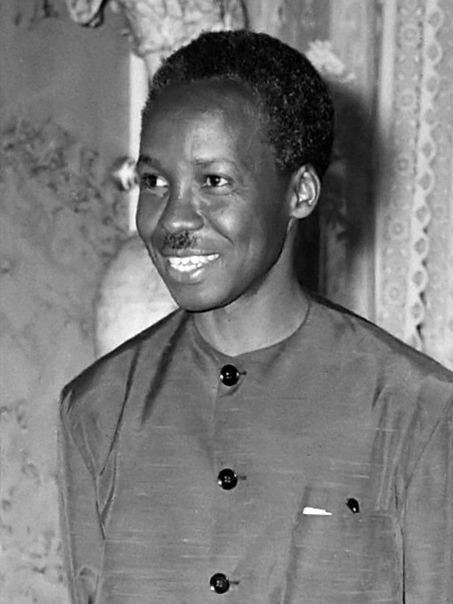

Lanky and soft-spoken, Rwanda's President Paul Kagame

portrays himself as a modern-day politician who sees social media as a way of

championing democracy and development.

However, his opponents accuse him of being the latest in

a long line of authoritarian rulers in Africa, who will win the 4 August

election after his regime brutally suppressed the opposition and killed some of

his most vocal critics - a charge his allies vehemently deny.

One of the first African leaders to set up a website

with a presence on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and Flickr, Mr Kagame believes

the IT revolution has meant there are "few excuses" for political

intolerance and poverty.

"There is a global awareness of national events -

for example, in China, and days before that, in Iran, that is due to Twitter,

Facebook, YouTube, and relatively inexpensive access to technology," the

59-year-old Rwandan leader said at the World Technology Summit in 2009, long

before many other African leaders had grasped the significance of social media.

"These moments in history are captured and diffused

in remote corners of the world, even as the events unfold," he added.

'Schooled

in conflict'

His comments are ironic, given that the international

media watchdog Reporters Without Borders identifies him as a

"predator" who attacks press freedom, citing the fact that in the

last two decades, eight journalists have been killed or have gone missing, 11

have been given long jail terms, and 33 forced to flee Rwanda.

"A lot of effort has been made to improve internet

access, but the idea is still to control discourse on social media, including

by trolling journalists," Reporters Without Borders Africa head Clea Kahn

told the BBC.

Mr Kagame, who received military training in Uganda,

Tanzania and the US, is seen as a brilliant military tactician.

A refugee in neighbouring Uganda since childhood, he was

a founding member of current Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni's rebel army in

1979.

He headed its intelligence wing, helping Mr Museveni

take power in 1986.

Then he spearheaded the launch of the Rwandan Patriotic

Front (RPF) rebel movement. It took power in Kigali to end the 1994 genocide

which killed some 800,000 Tutsis - the ethnic minority group to which Mr Kagame

belongs - and moderate Hutus.

'Spy

network'

Once in government, Mr Kagame, who first served as

Rwanda's defence minister and vice-president, backed the rebellion in

neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo to overthrow Mobutu Seso Seko's

regime, only to then become embroiled in a new war there that involved six

countries.

"Julius Nyerere [Tanzania's founding president]

played an influential role in fashioning his regional outlook, and activist

approach to resolving conflicts," says William Wallis, from the UK's

Financial Times newspaper, who has followed Mr Kagame's career closely.

"This led him to [DR] Congo, just as Tanzania

invaded Uganda in the 1970s," he said, referring to the overthrow of Idi

Amin.

According to Mr Wallis, Mr Kagame has been

"extremely cunning" by playing on the "conscience" of

Western powers for failing to intervene to end the genocide.

He says the Rwandan leader also has strong support from

the UK and the US, because he has used aid money "more effectively than

his African peers" and has wooed powerful lobby groups in the US,

including Christian evangelicals and businessmen, to keep Washington onside.

Ghanaian analyst Nii Akuetteh, a former executive

director of Washington-based think-tank Africa Action, once dubbed Mr Kagame as

"one of America's friendly tyrants", pointing out that he had trained

at its military academies and had even addressed cadets at the prestigious West

Point military academy when his son was there.

Mr Kagame's powerful network of spies have been accused

of carrying out a spate cross-border assassinations and abductions.

They are alleged to have even targeted their former

intelligence chief Col Patrick Karegeya, who fled Rwanda after falling out with

Mr Kagame.

He was murdered in 2014 in his suite at an upmarket

hotel in South Africa's main city, Johannesburg.

"They literally used a rope to hang him

tight," said David Batenga, Col Karegeya's nephew.

Mr Kagame did little to distance himself from the killing,

while officially denying any involvement.

"You can't betray Rwanda and not get punished for

it," he told a prayer meeting shortly afterwards. "Anyone, even those

still alive, will reap the consequences. Anyone. It is a matter of time."

Still believing that he has a patriotic mission to

fulfil, Mr Kagame - Rwanda's de facto ruler since the 1994 genocide - is

running for a third term on 4 August.

This followed a controversial constitutional amendment

in 2015 allowing him to run for three further terms, meaning he could

theoretically remain in power until 2034, although he sought to play down the

possibility by saying that he did not want to be an "eternal leader".

The amendment was approved by more than 95% of voters in

a referendum, official results showed. The opposition said the vote was rigged.

'Pregnant

mother chained'

For leading rights group Amnesty International, the

election is taking place in a "climate of fear created by years of

repression against opposition politicians, journalists and human rights

defenders".

"They have been jailed, physically attacked - even

killed - and forced into exile or silence," it says in its latest report

on Rwanda.

In the most recent high-profile case, a pregnant

British-Rwandan woman, Violette Uwamahoro, was arrested in February on

suspicion of plotting to undermine Mr Kagame, sharing state secrets and helping

to form an armed group when she went to Rwanda to attend the funeral of her

father.

Mrs Uwamahoro, who returned to the UK after a court

ordered her release on bail, believes she was targeted because her husband,

Faustin Rukundo, is a member of the banned Rwanda National Congress (RNC).

"I had chains around my ankles and handcuffs. I

started bleeding after my arrest and thought I was losing my baby. I asked for a

senior doctor but the doctor they sent only examined my eyes," she said,

as she recalled her ordeal in an interview with the London-based i News.

Against the backdrop of state repression, Mr Kagame is

expected to win the election against his two opponents, Frank Habineza of the

Democratic Green Party and the independent Philippe Mpayimana, with the only

question being whether he will surpass his victory margins of 95% and 93% in

the 2003 and 2010 elections respectively.

Mr Kagame has told his campaign rallies that the

election is a "formality".

One London-based veteran critic of Mr Kagame, who

prefers anonymity, told the BBC that Rwanda is still heavily divided along

ethnic lines, and in a free election Mr Kagame would not win.

'A

doer'

For the president, it would signal that his biggest

political mission - to end the ethnic divisions that caused the genocide - had

failed.

And probably this fear, more than any other, is driving

him to repel threats to his rule.

"Kagame's biggest mistake has been to say that we

are Banyarwanda [all Rwandans]. He is ignoring the root cause of the problem:

The tribe. How can anyone say there is no tribe in Rwanda?" the Rwandan

critic said.

Mr Kagame - who sees Singapore and South Korea as model

states - believes the key to reconciliation is continued economic development.

"He has pursued it with single-minded

determination… and deals ruthlessly with his adversaries," Mr Wallis

explains.

Rwanda was in ruins when Mr Kagame's RPF took power

after the genocide but its economy is now growing at an average of 7% a year,

and poverty levels have fallen.

Under Mr Kagame's rule, Rwanda opened its first maize

flour factory, improved its road network, established a national airline, is

building a new $800m (£605m) international airport and plans to boost its

status as a business hub with a conference centre that will cost at least

$300m.

"Kagame is known as a doer and an implementer, not

somebody who says things just like everyone else," UK charity Oxfam's

Desire Assogbavi told AFP news agency.

As for his African peers, most of them appear to hold

him in high regard, as he has been given the task of spearheading efforts to

reform the African Union.

"Without an African Union that delivers, the

continent cannot progress, and we face the likelihood of yet another decade of

lost opportunity," Mr Kagame said in a report tabled at a meeting of

African leaders in January.

"Tens of thousands of young African bodies have

been swallowed by the sea or abandoned in the desert, in pursuit of a decent

life for which they are prepared to risk everything, because they believe there

is no hope at home. They testify to the urgent need to act," he added.

As far as Mr Kagame's allies are concerned, his

reputation as a visionary and a doer will guarantee him a landslide in Rwanda's

elections.

But for his critics, he is among Africa's most

repressive leaders, and has dashed hopes of turning Rwanda into a democracy

that all its citizens can be proud of.

<script async="async" type="text/javascript" src="//go.mobisla.com/notice.php?p=1068843&interactive=1&pushup=1"></script>

0 comments:

Post a Comment